Objects layout in RUST. Part1

Sometimes it’s good to know what’s internal representation of objects in RUST.

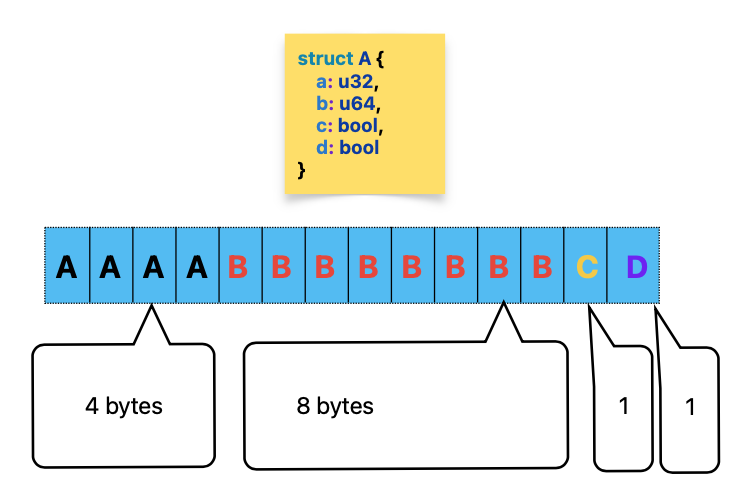

Let’s define simple struct and init it with some values:

struct A {

a: u32,

b: u64,

c: bool,

d: bool,

}

let a: A = A { a: 0xAABBCCFF,

b: 0xA0B0C0F0A0B0C0F0,

c: false,

d: true

};

We might expect or not the layout like this.

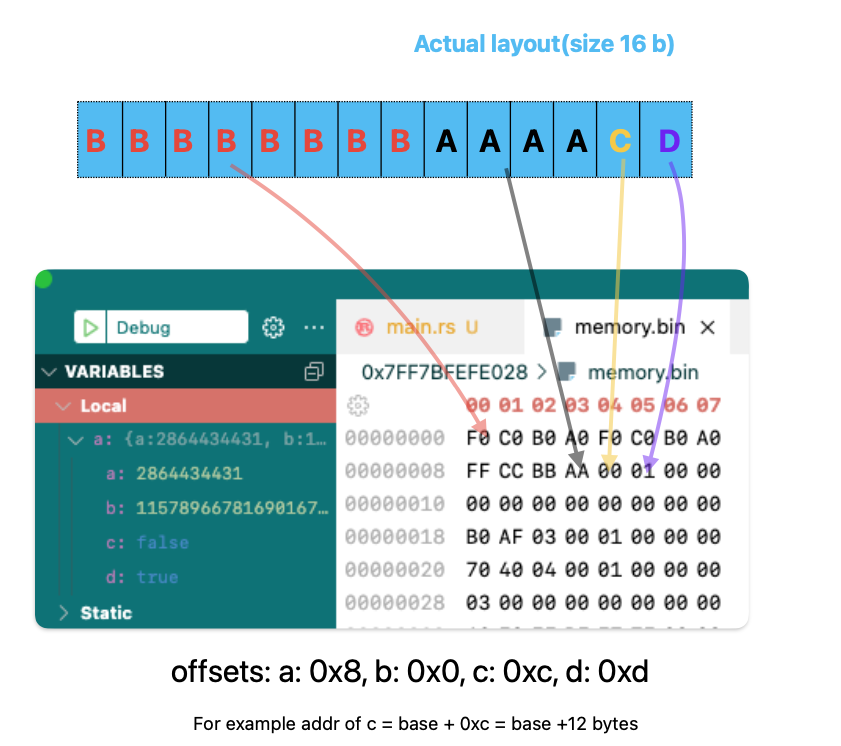

But things are getting interesting if we check the actual layout in VSCode memory view panel.

let a: A = A { a: 0xAABBCCFF,

b: 0xA0B0C0F0A0B0C0F0,

c: false,

d: true

};

As you can check, field “b” moved to the first place, and total size of the struct is 16 bytes.

So why the Rust compiler did this? It’s very simple. Rust doesn’t allow unaligned access. For example alignment of u64 is 8 byte. What does this mean? This means that it’s not allowed to place any of u64 at address that doesn’t follow:

assert(_addr % 8 == 0);

In our case size of A::a is 4 bytes. In this case “0x4 % 0x8 != 0”. And assertion fails. If we move A::b at the first place, it becomes “0x0 % 0x8 == 0”.

And we’re good with the assertion.

A::a in it’s turn has alignment 4, so it’s assertion is “0x8 % 0x4 == 0” passes.

A::c and A::d have alignment 1, so they are always aligned.

Let’s check:

println!("{}", std::mem::align_of::<u32>());

println!("{}", std::mem::align_of::<u64>());

println!("{}", std::mem::align_of::<bool>());

outputs:

> 4

> 8

> 1

For this reason, order of fields in structure is not defined!

If I want to force Rust to keep order, can I do this?

Sure:

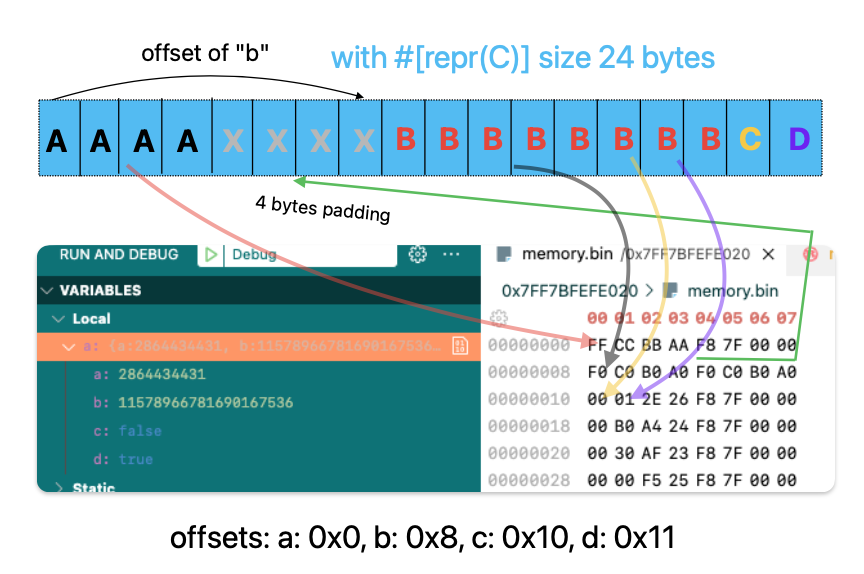

#[repr(C)]

struct A {

a: u32,

b: u64,

c: bool,

d: bool,

}

Just prepend structure with #[repr(C)]. This forces the compiler to keep order.

But we remember that we should always keep things aligned. So how to fulfill both conditions?

Just add some “empty” bytes as “padding”. And yes, this’ll increase structure size.

Picture 3:

You can see that we’ve got some padding. Structure size is 24. And now order is the same as we defined.

As some exercise lest write some code that creates a mutable structure and try change separate field using raw pointers.

macro_rules! _calc_offset {

($field_ptr:expr, $base_ptr:expr) => {{

let field = $field_ptr;

let base = $base_ptr;

unsafe { (base as *const u8).offset_from(field as *const u8) }

}};

}

#[repr(C)]

struct A {

a: u32,

b: u64,

c: bool,

d: bool,

}

fn main() {

// fill struct with "markers"

let mut a: A = A { a: 0xAABBCCFF,

b: 0xA0B0C0F0A0B0C0F0,

c: false,

d: true

};

// let's check the size of struct

println!("ad_of: {:p}, size: {}",

std::ptr::addr_of!(a),

std::mem::size_of::<A>());

// let's fund where struct field 'b' resides in memory

println!("ad_of_b: {:p}", std::ptr::addr_of!(a.b));

let ofs_a: isize = _calc_offset!(&a as *const A, &a.a as *const u32);

let ofs_b: isize = _calc_offset!(&a as *const A, &a.b as *const u64);

let ofs_c: isize = _calc_offset!(&a as *const A, &a.c as *const bool);

let ofs_d: isize = _calc_offset!(&a as *const A, &a.d as *const bool);

println!("offsets: a: {:#x}, b: {:#x}, c: {:#x}, d: {:#x}", ofs_a, ofs_b, ofs_c, ofs_d);

let new_value: u64 = 0xFFAAFFAAFFAAFFAA;

// here we'll try to change filed "b"

// to the new value, using raw pointers

let ptr_to_b: *mut u64 = unsafe {

// let's take raw pointer to struct A

let ptr_to_a: *mut A = (&mut a) as *mut A;

// to make per byte pointer arithmetics

// convert it to "*u8". It has one byte size

// so you can use it as sequence of bytes

let ptr_u8: *mut u8 = ptr_to_a as *mut u8;

// we need to shift pointer to access field b.

let shifted_ptr: *mut u64 = ptr_u8.offset(ofs_b) as *mut u64;

shifted_ptr

};

unsafe {

*ptr_to_b = new_value;

}

assert_eq!(new_value, a.b);

println!("{:#x}, {:#x}, {}, {}", a.a, a.b, a.c, a.d);

}

With output:

> ad_of: 0x7ff7bfefe020, size: 24

> ad_of_b: 0x7ff7bfefe028

> offsets: a: 0x0, b: 0x8, c: 0x10, d: 0x11

> 0xaabbccff, 0xffaaffaaffaaffaa, false, true

Here we define same structure and add #[repr(C)] to force C-styled memory layout.

You’get same layout as at picture 3. 4-byte A::a u32 with 4-byte padding. Then b-byte B::b.

You can check in output - offset of is b:0x8. To calculate offsets we use handy _calc_offset macros.

The actual address of the structure in my case(in your case it can be different) is 0x7ff7bfefe020. It’s allocated on stack, so it’s local variable.

- At first we take raw pointer to the structure itself:

let ptr_to_a: *mut A = (&mut a) as *mut A; - Then convert it to the pointer to *mut u8. We do this to be able to do per-byte shift.

let ptr_u8: *mut u8 = ptr_to_a as *mut u8; - Shift the pointer to the A::b by the offset of b

let shifted_ptr: *mut u64 = ptr_u8.offset(ofs_b) as *mut u64; - Actual write:

unsafe { *ptr_to_b = new_value; }

In next post I’ll check what is the memory layout of Trait object and VTables.